The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - The Amygdala's Role in Amplifying Self-Doubt

Within the intricate network of the brain, the amygdala stands out as a pivotal component in our emotional landscape, particularly when it comes to fear and feelings of inadequacy. Its extensive connections to other brain regions play a significant role in how we perceive social situations and assess our own skills. It's through these connections that the amygdala influences emotional responses, contributing to how we feel about ourselves.

A heightened state of activation in the amygdala can exacerbate feelings of imposter syndrome, making it challenging to overcome self-doubt. This heightened activity can amplify feelings of inadequacy, creating a persistent loop of negative self-perception. Adding to the complexity, the amygdala is instrumental in forging powerful memories, especially those associated with stressful events. These memories can become intertwined with our current sense of self, making it difficult to separate past experiences from our present perception of our abilities.

Gaining a deeper understanding of the amygdala's influence on self-doubt could offer valuable insights into developing strategies for managing and overcoming these persistent feelings. This knowledge could contribute to a more balanced and positive perspective on our capabilities.

The amygdala, while often labeled the "fear center," seems to play a broader role in emotional processing, extending beyond fear to include the anxieties intertwined with imposter syndrome. This suggests its involvement in self-doubt goes beyond simple threat response.

Intriguingly, the amygdala can become active even when no apparent external danger exists, suggesting it can fuel self-doubt as a reaction to internal thoughts and mental processes, not solely to external situations. This raises questions about the interplay between internal mental chatter and amygdala reactivity.

Individuals exhibiting elevated amygdala activity appear to be more susceptible to negative self-assessments. This correlation with feelings of inadequacy, a key feature of imposter syndrome, is noteworthy, implying a possible neurological foundation for these subjective experiences.

Research even indicates a possible link between amygdala size and self-doubt tendencies. Some studies suggest larger amygdalae may be associated with elevated anxiety and diminished self-esteem. However, it is important to note that this connection is still under investigation and far from conclusive.

Furthermore, the amygdala's extensive network of connections with regions responsible for decision-making and social perception suggests that our self-doubt might not only stem from individual interpretation but also be influenced by societal and interpersonal expectations. This points to the possibility that our sense of self-worth is shaped by a complex interplay between our own minds and social environments.

Dysfunctions within the amygdala's communication pathways could result in exaggerated responses to perceived failures, intensifying self-doubt and sustaining the cycle of imposter syndrome. Understanding these pathways might reveal potential therapeutic avenues.

Neurological studies using imaging techniques reveal a curious pattern in individuals grappling with imposter syndrome. Their amygdala shows heightened activity when reflecting upon their own achievements, indicating a unique neurological response to positive feedback. Why the brain reacts this way when experiencing success needs further exploration.

The potential influence of genetics on amygdala function adds another layer to the puzzle. It's possible that inherent variations in amygdala activity due to genetic predispositions might make some individuals more vulnerable to self-doubt, hinting that imposter syndrome may have biological roots beyond learned behaviors.

The amygdala's role in emotional memory also appears relevant to self-doubt. Negative experiences or past failures might be easily recalled, potentially fueling a continuous loop of self-questioning and undermining confidence. Understanding how these memories are stored and accessed by the amygdala could be a crucial step in addressing these persistent feelings.

Ultimately, a deeper understanding of the amygdala's contribution to self-doubt could lead to the development of innovative therapeutic strategies. Targeting the amygdala, with methods like cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness practices, could offer new avenues for helping people combat the incapacitating effects of imposter syndrome and cultivate more stable self-assurance.

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - Prefrontal Cortex Function and Cognitive Distortions

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), often considered the brain's command center, is crucial for cognitive control—the ability to guide our thoughts and actions toward our goals. This brain region, viewed as the most advanced part of our brain, underpins our higher-level thinking skills, including the ability to hold information in mind (working memory), focus our attention, and organize our behaviors. The PFC acts like a conductor, ensuring other parts of the brain work in concert to achieve our intentions.

However, the PFC's intricate dance of mental orchestration can be disrupted. Stress, even in mild forms, can significantly impact the PFC's structure and function, compromising its ability to effectively manage our cognitive resources. This vulnerability makes the PFC particularly susceptible to the negative effects of stress and can lead to errors in thinking (cognitive distortions). These distortions, often seen in conditions like imposter syndrome, can create a skewed self-perception, making it difficult to accurately assess our own abilities.

Cognitive distortions can arise from the PFC's struggle to process information correctly, particularly when it comes to achieving goals and interpreting successes. This can result in a disconnect between reality and our internal narrative, feeding feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt. By delving into the intricacies of the PFC's function, particularly how it processes achievements, we can potentially find new strategies to help individuals manage imposter syndrome and foster a more balanced self-image. Ultimately, a better understanding of how this part of the brain works could guide efforts to improve mental well-being and build stronger, more resilient self-esteem.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), often considered the brain's command center, plays a crucial role in cognitive control, essentially orchestrating our mental processes to align with our present goals and future plans. It's considered the most advanced brain region, responsible for higher-level thinking like working memory, focused attention, and organizing our behavior. This cognitive control relies on the PFC actively maintaining goals, which then guides processing in other parts of the brain, ultimately enhancing goal-oriented actions.

While the exact functional divisions within the PFC are still a bit hazy, research suggests these regions may work together in a hierarchical manner rather than each having a unique, singular function. Interestingly, the PFC's role extends across a wide range of cognitive processes, influencing the interplay between our deliberate actions and more automatic thought patterns.

It's worth noting that the PFC is surprisingly sensitive to stress. Even brief, mild stress can swiftly diminish our cognitive abilities. This sensitivity highlights its vulnerability compared to other brain regions. Studies in humans and rhesus monkeys, using brain imaging, have shown that certain PFC regions, like the anterior ventrolateral part, are engaged in working memory tasks.

This brings us to cognitive distortions. These distorted thought patterns, commonly observed in situations like imposter syndrome, may be linked to faulty processing within the PFC. In essence, the PFC's executive functions, impacting our cognitive performance and self-perception, are central to understanding how we perceive ourselves.

For example, cognitive distortions can stem from biased thinking. If we overgeneralize our failures or dismiss our successes, it can create a distorted view of our abilities. The PFC is normally involved in what we could call "reality testing," allowing us to evaluate our thoughts against evidence. However, dysfunction in this area can impair our ability to challenge these negative thoughts effectively.

The PFC's role in managing emotions is also relevant. When experiencing self-doubt or stress, the PFC may not function optimally, potentially resulting in an increase in negative self-talk and perpetuating the cycle of cognitive distortions. It's fascinating that the PFC, unlike many other areas, demonstrates considerable neuroplasticity. It can adapt and restructure its connections and pathways in response to learning or experience. This hints that therapeutic interventions aimed at improving PFC function might be useful in reducing the impact of negative thoughts in imposter syndrome.

Another facet of this relationship involves impulsivity, which has been linked to PFC dysfunction. Individuals with impaired PFC function may act on negative thoughts without proper reflection. This can worsen feelings of inadequacy and reinforce cycles of self-doubt. When faced with complex tasks, the PFC can get overwhelmed and tend to rely on mental shortcuts. This can lead to inaccurate judgments and potentially heighten the experience of feeling like an imposter, particularly under pressure.

Interestingly, mindfulness practices have been observed to activate the PFC, improving its ability to regulate emotions and potentially offering a pathway to mitigate cognitive distortions. There's also evidence suggesting that genetic factors, such as variations in dopamine pathways, can influence PFC activity, possibly predisposing certain individuals to increased sensitivity to self-doubt and distorted thinking.

Finally, the PFC is involved in anticipating future outcomes. When these predictions are skewed by distorted thinking, it can lead to anticipatory anxiety. Individuals experiencing imposter syndrome may worry about failing even before they've encountered a challenging situation, further fueling the feeling of being an imposter. Understanding the intricacies of the PFC and its interplay with our thoughts, behaviors, and emotional responses holds significant potential for developing new strategies to manage and potentially alleviate conditions like imposter syndrome. It's a testament to the brain's complexity and its intricate role in our perception of ourselves and the world around us.

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - Neuroplasticity and the Reinforcement of Imposter Thoughts

Our brains possess an incredible capacity for change, a property known as neuroplasticity. This means the brain can adapt and restructure its neural pathways based on our experiences. This inherent flexibility can either solidify negative thought patterns associated with imposter syndrome or provide a path toward healthier self-perception.

When we encounter stressful events or repeated experiences of self-doubt, the brain's plasticity can contribute to the strengthening of neural networks that perpetuate imposter thoughts. These reinforced patterns can become entrenched, making it difficult to break free from the cycle of negative self-evaluation.

However, understanding this adaptable nature of the brain also offers hope. Neuroplasticity suggests that it's possible to rewire the brain, particularly the connections involved in negative thought cycles associated with imposter syndrome. By actively adopting strategies that encourage neuroplastic changes, it may be feasible to weaken detrimental thought patterns and foster a more positive and resilient self-image. The brain's ability to reshape itself highlights the possibility of overcoming self-doubt and building a stronger sense of self-worth through conscious and deliberate effort.

The brain's capacity for change, known as neuroplasticity, is a key factor in how imposter syndrome takes hold. Our brains are constantly rewiring themselves based on our experiences, and if we frequently engage in negative self-talk, it can strengthen those neural pathways associated with self-doubt, making it easier to fall into that pattern. It's like a well-worn groove in the brain – the more we traverse it, the deeper it becomes.

The hippocampus, essential for memory formation, interacts closely with both the amygdala (our emotional center) and prefrontal cortex (our higher-level thinking center). This means the way we remember our achievements or failures plays a significant role in how susceptible we are to imposter thoughts over time. Our memories are not just static snapshots; they are shaped by neuroplasticity, constantly being reinterpreted and reinforced.

Recent research suggests even short periods of mindfulness practice can stimulate neuroplasticity in the prefrontal cortex. This increased adaptability can help counter the inflexible thinking often associated with imposter syndrome, suggesting it could be a valuable tool in therapeutic interventions. It's fascinating how something as simple as being present in the moment might be able to help change the way our brains respond to negative thoughts.

Neuroplasticity also involves a process called "neural pruning," where unused connections are gradually eliminated. If we don't actively challenge our negative self-perceptions, those pathways can be pruned, making it harder to break free from those ingrained patterns later on. It's akin to letting a garden grow wild—if we don't tend to it, it might become overgrown and difficult to manage.

Consistent experiences of perceived failure can alter the brain's reward system. When negative experiences outweigh the positive ones, the brain can rewire itself to respond with self-doubt and fear instead of confidence. It's as though the brain prioritizes avoiding further negative experiences, resulting in a behavioral shift towards self-protection.

Neurofeedback techniques offer a potential avenue to leverage neuroplasticity by allowing individuals to visualize their brain activity in real-time. This approach can help the brain recognize and shift away from the self-critical thoughts linked to imposter syndrome. The idea is that by seeing the patterns, one can develop new ones.

Intriguingly, actively engaging in positive self-affirmations can instigate neuroplastic changes, potentially challenging entrenched beliefs about our inadequacy and promoting a more balanced self-view. It's like trying to retrain a plant's growth by physically guiding its direction.

The striatum, part of the brain's reward system, is also subject to neuroplasticity and significantly affects how we perceive and reward our successes. If there's a disconnect in this system, we might downplay our accomplishments, exacerbating the feelings of being a fraud. This could hint at a disharmony within our brain's internal reward mechanism.

Genetic predispositions can impact neuroplasticity, influencing how susceptible individuals are to the long-term effects of past experiences on their self-perception. Variations in genes related to dopamine pathways, for instance, might increase that vulnerability. It's like having a garden with different soil types—some plants might thrive, while others may struggle.

Finally, consistently engaging in activities that challenge self-doubt—such as public speaking or taking on leadership roles—can physically reshape the brain through neuroplasticity, lessening the hold of imposter thoughts and fostering greater confidence over time. It's a testament to the incredible adaptability of the brain, that through consistent effort, we can literally rewire the way we think about ourselves.

This exploration highlights the dynamic interplay between our experiences, our biology, and our thoughts. By understanding how neuroplasticity influences the reinforcement of imposter thoughts, we can potentially develop strategies to harness the brain's remarkable capacity for change and foster greater self-acceptance.

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - Stress Hormones and Their Impact on Brain Chemistry

Stress hormones, like cortisol and other glucocorticoids, profoundly influence brain chemistry and how we experience emotions and think. These hormones target key brain areas such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, affecting our ability to form memories and regulate emotions. When we experience prolonged stress, it can alter the very structure and connectivity of brain cells, especially in the prefrontal cortex. This can hinder the prefrontal cortex's ability to manage cognitive functions efficiently. This vulnerability of the prefrontal cortex to stress is potentially a significant factor in how we develop and maintain negative self-perceptions. This relationship between stress, hormone levels, and our self-doubt suggests a strong link between stress-related brain changes and the experience of imposter syndrome. Gaining a better understanding of this complex interplay can lead to innovative approaches for treating the adverse impacts of stress on our mental health and self-worth.

Here's a look at how stress hormones and brain chemistry intersect, especially in the realm of self-doubt and imposter syndrome:

Firstly, cortisol, often considered the 'stress hormone', plays a complex role in cognition. While acute stress can improve memory, especially for emotionally intense events, chronic high cortisol can hinder memory retrieval and cognitive function. This can make it harder for individuals to recognize their own accomplishments.

Secondly, stress hormones like cortisol can interfere with the brain's neurotransmitter balance, particularly serotonin, a vital player in mood regulation. Reduced serotonin can contribute to increased anxiety and self-doubt, reinforcing negative thought patterns.

Thirdly, consistent exposure to stress hormones can increase the amygdala's sensitivity, leading to an overblown fear response. This amplified activity can make feelings of inadequacy and anxiety—common features of imposter syndrome—even more intense.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, activated during stress, releases cortisol and increases cognitive load. This physiological response can interfere with the prefrontal cortex's decision-making abilities, contributing to distorted self-perception.

Interestingly, chronic stress increases pro-inflammatory cytokines. These inflammatory markers are associated with impaired neurogenesis in the hippocampus, which can further hinder memory and learning. These are crucial for overcoming feelings of self-doubt.

The relationship between stress hormones and brain chemistry can form self-reinforcing loops. For example, low self-esteem might trigger stress responses that raise cortisol levels, which can then perpetuate more negative self-perceptions.

Individual responses to stress hormones can vary due to genetic differences in the glucocorticoid receptor gene. This genetic variation might make some people more prone to heightened feelings of inadequacy during stressful situations, potentially increasing vulnerability to imposter syndrome.

Elevated stress hormones can negatively impact sleep quality, leading to fragmented sleep. Insufficient quality sleep impacts cognitive function and emotional regulation, further exacerbating feelings associated with self-doubt.

Despite often having detrimental effects, acute stress can also spur neuroplasticity in certain circumstances. This suggests that while stress can be damaging, it can also become a driver for growth if managed effectively.

Social situations, particularly those involving evaluation, can lead to greater increases in cortisol compared to physical stressors. This emphasizes the profound impact social settings have on our emotional regulation and sense of self-worth.

These findings highlight the intricate interplay between stress hormones, brain chemistry, and self-perception. They also underscore the importance of developing strategies to increase resilience and counter the detrimental effects of imposter syndrome.

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - Neural Networks Involved in Self-Perception and Evaluation

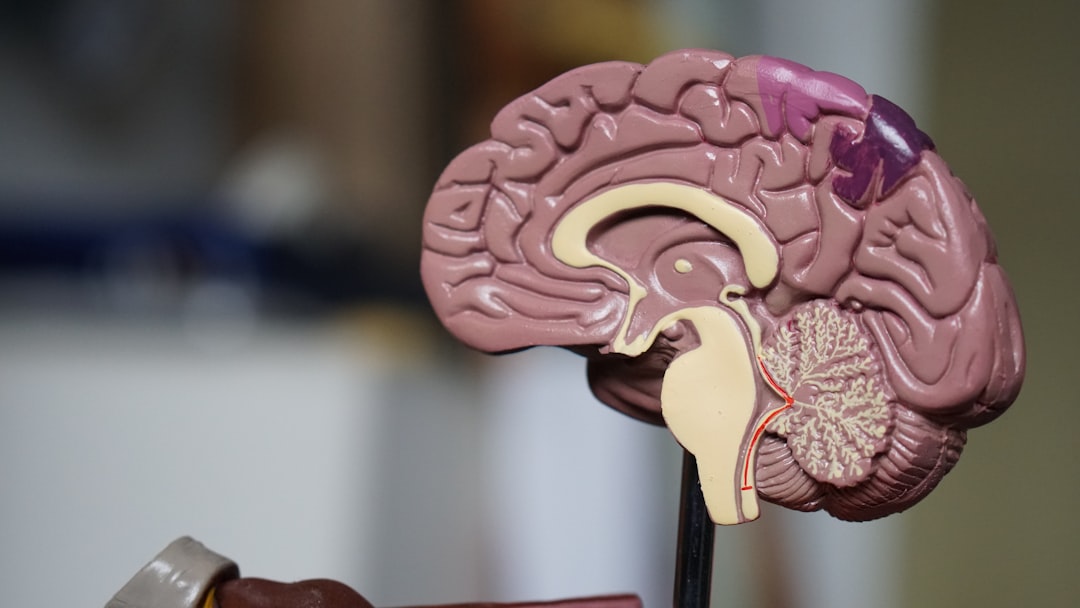

Neural networks play a pivotal role in how we perceive and judge ourselves, which becomes particularly important when considering imposter syndrome. Brain regions like the prefrontal cortex, responsible for higher-level thinking, and the default mode network, which integrates our internal and external experiences, contribute to our self-awareness and how we regulate emotions in social contexts. However, the intricate workings of how we positively evaluate ourselves are still poorly understood, creating questions about how biases and memory influence our self-image.

Brain imaging has helped us begin to unravel this intricate puzzle. The hope is that by understanding how these neural networks interact, we can gain more insight into how self-esteem works and potentially develop better ways to help people lessen their feelings of inadequacy. The complexity of these neural interactions highlights that there's much more to uncover about how the brain shapes self-perception and makes us susceptible to distorted self-views. This is an area that requires further investigation to fully comprehend the multifaceted nature of self-perception and the brain's contribution to it.

The brain's intricate network plays a vital role in how we perceive and evaluate ourselves. Research suggests that the default mode network (DMN), a group of brain regions active during introspection, is central to self-identity. This network involves areas like the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), which can become overly active in those grappling with imposter syndrome, leading to a cascade of self-critical thoughts.

Interestingly, some studies point to a possible imbalance in prefrontal cortex activity between the two hemispheres in individuals experiencing imposter syndrome. This asymmetry may influence how they regulate emotions and control their thoughts, contributing to distorted self-assessments and intensified self-doubt.

The striatum, a brain region crucial for processing reward and motivation, seems to be less responsive to achievements in those with imposter syndrome. When this system doesn't provide the usual positive reinforcement for accomplishments, it may fuel feelings of inadequacy, reinforcing a cycle where success is met with internal doubt.

Mirror neurons, which are involved in understanding others and empathizing, might also be implicated. These neurons could potentially misfire in those experiencing imposter syndrome, leading to difficulties accurately comparing oneself to others, fostering a feeling of disconnect and being an "imposter" among peers or in professional settings.

The link between autobiographical memories and imposter syndrome is also gaining attention. Individuals with imposter syndrome might struggle to retrieve positive memories, possibly due to issues in the communication between the hippocampus (memory formation) and the prefrontal cortex. This could create a situation where they overlook or undervalue past successes, hindering their ability to counter negative feelings associated with current achievements.

Furthermore, neurochemicals like dopamine and serotonin could play a significant role in how we evaluate ourselves. A deficit in serotonin could exacerbate self-doubt, while irregularities in dopamine could interfere with the brain's reward system, further hindering the ability to recognize and celebrate personal achievements.

Cognitive load, the mental effort required to process information, is also a factor. When faced with demanding tasks or stressful evaluation, the prefrontal cortex may struggle to manage emotions and accurately process self-related information. This makes individuals more susceptible to cognitive distortions and skewed perceptions of their own abilities.

Brain regions like the temporal lobes, involved in processing social and emotional cues, demonstrate heightened activity in those experiencing imposter syndrome. This suggests a potential over-processing of social interactions and self-referential information, leading to a predisposition to negative self-assessments.

Mindfulness practices, which focus on cultivating present-moment awareness, can boost the brain's flexibility, particularly in the prefrontal cortex. This neuroplasticity can help counteract the rigid thought patterns common in imposter syndrome, implying that these practices might offer a pathway to healthier self-perception.

Lastly, genetic predispositions might play a role in susceptibility to imposter syndrome. Variations in genes controlling neurotransmitter systems, such as the serotonin transporter gene, may contribute to increased vulnerability to the cognitive distortions seen in this phenomenon, illustrating the complex biological basis of this experience.

This area of research highlights the intricate and interconnected nature of the brain in our self-perception. By delving further into these neural mechanisms, scientists hope to develop more effective ways to help individuals overcome self-doubt and develop a healthier and more resilient sense of self.

The Neuroscience Behind Imposter Syndrome Unveiling the Brain's Role in Self-Doubt - Dopamine Reward System Dysfunction in Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome's link to a dysfunction in the dopamine reward system is gaining attention, especially when considering how individuals process their successes. The dopamine reward system, vital for recognizing and reinforcing positive outcomes, seems to function differently in individuals with imposter syndrome. Instead of feeling rewarded for accomplishments, they may struggle to acknowledge or internalize their achievements, possibly attributing their success to luck or external factors. This leads to a feeling of inadequacy and a decreased sense of personal efficacy. The inability to properly integrate the rewards associated with success can reinforce feelings of being a fraud.

A clearer grasp of this dopamine system dysfunction could guide the development of more specific interventions for people with imposter syndrome. Understanding these neurobiological mechanisms opens avenues to potentially change the brain's wiring in a way that fosters more accurate self-perception and promotes a stronger, more internally based sense of achievement. The research into this area is important for a more holistic view of imposter syndrome, suggesting new paths for treating the core psychological issue. It also underscores that addressing self-doubt might necessitate addressing the reward system's functioning.

Imposter syndrome, characterized by persistent self-doubt despite evident accomplishments, may be linked to a dysfunction in the brain's reward system, particularly concerning dopamine. Dopamine, a neurochemical instrumental in processing pleasure and motivation, appears to have a reduced impact on individuals with imposter syndrome. This diminished response to achievement can make it difficult to experience satisfaction or fulfillment from successes, leading to a feeling of inadequacy that fuels the syndrome.

Interestingly, this dopamine dysfunction may disrupt the connections between the striatum, a region involved in reward processing, and the prefrontal cortex, which governs higher-level thinking and decision-making. This disruption can make it difficult to objectively assess one's achievements, magnifying self-doubt and reinforcing the internal narrative of being a fraud.

Social comparison, a common human tendency, can also exacerbate imposter syndrome in individuals with this dopamine-related vulnerability. Studies indicate that social comparisons typically trigger dopamine release, but individuals with imposter syndrome may exhibit lower dopamine responses when comparing themselves to peers. This reduced dopamine surge, in the context of social comparison, can increase the intensity of feelings of inadequacy and further entrench the imposter feelings.

This imbalance in dopamine signaling can create a negative feedback loop where individuals repeatedly undervalue their successes. Positive experiences, rather than being enjoyed and celebrated, are dismissed or interpreted as coincidences. This constant downplaying of accomplishments perpetuates the cycle of self-doubt, reinforcing the core belief that one is undeserving of their achievements.

The interaction between dopamine and serotonin, another neurotransmitter involved in emotional regulation, also appears significant. Reduced levels of serotonin, often linked to anxiety and depression, can further intensify the feelings of insecurity and self-doubt experienced in imposter syndrome, when combined with a dysfunctional dopamine system.

Furthermore, there's evidence that genetic variations might predispose individuals to imposter syndrome by influencing the sensitivity of dopamine receptors in the brain. This genetic component suggests that biological factors, in addition to psychological ones, might play a role in vulnerability to this experience.

Chronic stress, with its associated release of stress hormones, can also exacerbate the dopamine system's dysfunction. Elevated stress hormones can disrupt dopamine pathways, impairing the brain's ability to process rewards effectively. This disruption can further complicate the cycle of imposter syndrome by making it even more challenging to appreciate successes and mitigate self-doubt.

This dopamine dysfunction can also hinder cognitive flexibility. Individuals may struggle to modify their thinking patterns and adapt to new experiences, making it harder to challenge the negative self-beliefs central to imposter syndrome. This rigid thinking makes it challenging to overcome the persistent feelings of inadequacy.

Thankfully, a greater understanding of the role of the dopamine reward system in imposter syndrome presents exciting possibilities for targeted therapeutic interventions. Dopamine-enhancing therapies, though still in early stages of research, are one potential avenue for alleviating these symptoms. Behavioral strategies, such as reframing perceptions of success and fostering greater self-compassion, might also offer helpful pathways to change these reward responses over time.

Mindfulness, with its emphasis on present-moment awareness and emotional regulation, shows potential to improve dopamine function gradually. This may assist individuals with imposter syndrome in reframing their experiences of success, leading to enhanced well-being and a more balanced self-perception.

While the intricate connections between the brain's reward system and imposter syndrome are still being explored, the evidence suggests a significant role of dopamine dysfunction in the cycle of self-doubt. A better understanding of this complex interplay holds promise for developing more effective therapeutic interventions aimed at helping individuals break free from the grip of imposter syndrome and cultivate a healthier, more resilient self-image.

More Posts from psychprofile.io:

- →The Evolving Landscape Where Therapists Can and Cannot Prescribe Medication in 2024

- →Bottom-Up Processing in AI Mimicking Human Sensory Perception for Enhanced Enterprise Decision-Making

- →How Neuroticism Levels Influence Decision-Making Speed in High-Pressure Situations

- →Understanding the Role of Gender Identity Therapists in Mental Health Treatment Recent Clinical Findings and Best Practices

- →Understanding LGBT Trauma Local Therapists Provide Healing Paths

- →7 Evidence-Based Therapy Approaches Gaining Traction Among Williamsport Mental Health Professionals in 2024